A number of years ago I met with several leaders to determine a strategy for improving the performance of their operations. The discussion started with the high-level goals of the organization and the general direction of the team. As the conversation continued, the topics became very granular, with even minute process details being dictated by the senior leader in the room. He had a very specific plan for the operation that he wanted to see implemented.

After discussing the details of the new process, the topic of conversation turned to rolling the changes out to the staff. As a team, we all agreed that getting staff input would be a valuable part of the improvement process. There was less agreement on what that staff input should look like.

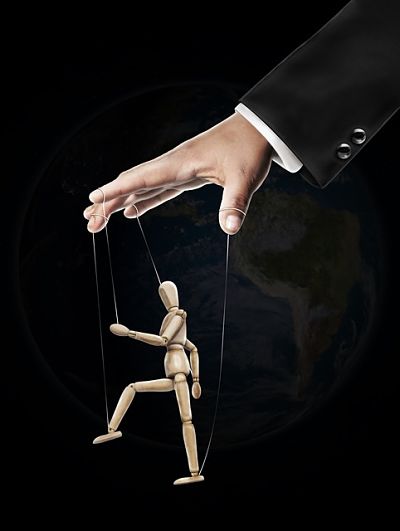

The senior leader described a series of meetings with front line staff in which it was the job of the area leader to present the new process and ask for staff input. He stressed that the point of the meetings was to make sure the staff “feel involved” in the process. He wanted their buy-in, while still making sure it was his process that was implemented.

My heart sank at this. He missed the point. Having control of the situation was more important to him than involving the staff in a genuine way.

Even when leaders seem to grasp the importance of involving front line staff in improvement work, they don’t always get it right. This is usually due to a misunderstanding of the goals and benefits of this approach to improvement.

Benefits of Staff Involvement

Improved Acceptance of Change – It is no secret that individuals are much more likely to buy-in to ideas when they are involved in their creation or refinement. Involvement creates a sense of shared ownership that increases the desire to make the change successful.

This is the most obvious benefit to involving front line staff in the improvement process, so this is the one that most leaders focus on. Unfortunately, this focus can prevent them from seeing and taking advantage of several other key benefits of staff involvement.

Better Solutions – Front line staff are the individuals that know their work the best. They can see ways in which solutions can be improved because they know the intricate details of the work. This intimate knowledge allows them to identify problems that will prevent a change from being successful and propose solutions to help ensure success.

There can also be a benefit due to the number of people involved. By involving front line staff in the decision making process, there are more minds working on the problem. More perspectives, more diverse experiences, more brainpower. The more people are involved, the more likely it is that someone will generate a creative solution. Great ideas can come from anywhere, not just leadership.

Development Opportunities – A commonly overlooked benefit of involving more people in the improvement process is the personal development experienced by those involved. Every problem solving opportunity is also a great learning opportunity. The experience of working with a team to solve a problem and implement a solution can create and refine transferable skills that are desirable in all employees. The growth involved can also create a sense of accomplishment in individuals above and beyond what comes from the improvement itself.

Organizations as a whole also benefit from this development. Individuals who are skilled at problem solving will provide significant value to their organizations as they continue solving future problems. Developing this skill across the workforce also increases the likelihood of developing individuals with the skills necessary to succeed in leadership positions. Teaching everyone problem solving skills can be a great first step in internal leadership development.

Two Common Mistakes

Over the years I have seen leaders make many mistakes when trying to involve front line staff in improvement efforts. The overwhelming majority have fallen into one of these two categories.

Insincere Involvement – When leaders are primarily focused on the benefit of acceptance, the tendency is to shape staff involvement efforts to meet that goal. The result is often an effort that is insincere. This can come across in several ways.

Sometimes leaders will ask for staff ideas with no intention of acting on them. Other times, plans are made without staff involvement and then they are given the chance to provide feedback at the last minute, frequently when it is too late to make any significant changes. At its worst, this behavior can involve manipulative behavior from leaders in which the staff are forced down a certain path but made to think it was their own idea.

Lack of Guidance – On the opposite end of the spectrum are the leaders that give front line staff too much freedom in solving problems. The thought process is that if involving staff in the improvement process is such a good thing, more should be even better. These situations typically involve leaders putting the entire burden of improvement on the staff, with little to no guidance.

If the individuals are not already skilled problem solvers, they quickly become frustrated, make little progress, or propose poor solutions. The end result is a lack of successful improvements and little to no valuable learning for the individuals involved.

A Better Way

Ideally, leaders will walk the line between these two extremes when the attempt to involve staff in improvement efforts. This is not an easy task. It requires significant amounts of time and energy, but the benefits are well worth it. Here are a few ways in which this can be accomplished.

Set Boundaries – Leaders should clearly define the boundaries within which process improvement teams should operate. Be transparent about what is up for discussion and what is not. This will allow teams to focus on the areas where their input is needed, rather than wasting time discussing ideas that will never be accepted. It also shows respect to the individuals involved by dealing with them openly and honestly. It is better to provide a clear no upfront, so that there is not confusion about the expectations.

Allow Freedom Within Boundaries – Once the boundaries have been clearly defined, leaders should be committed to allowing the team freedom within those limits. This means allowing the team to make decisions and experiment, even when their ideas do not line up with the leader’s ideas. Empowering your front line staff to make decisions and even make mistakes will provide them with opportunities to learn and grow.

Coaching – To take full advantage of these learning opportunities, they should be coupled with active coaching throughout the improvement process. Leaders should provide team members with feedback and guidance that steers them towards a solid solution. Not the solution desired by the leader, but one that does solve the problem at hand.

This coaching should include instruction on the problem solving process, guidance on problem definition and risk analysis, and probing questions to strengthen the thinking of the team. If leaders successfully coach their staff through a defined process, the end result should be a solid improvement effort.

With the proper approach to staff involvement, improvement efforts can deliver a wide variety of benefits to your organization. Over time, you will be able to develop a workforce of individuals that are fully capable of solving problems and driving improvement efforts with little to no oversight, ensuring the long-term success of your organization.